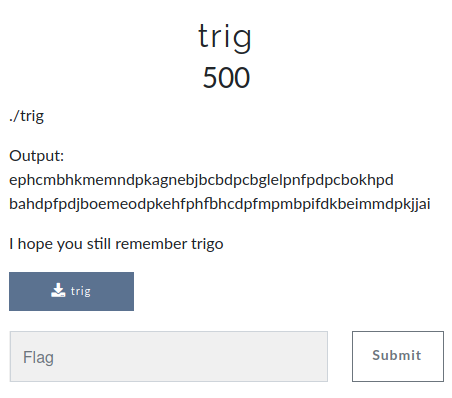

The CyberSecurity Club IITB conducts an yearly CsecCTF. This was also my first CTF. There were many interesting questions but the one we were not able to solve until the final moments was trig. Luckily, we were able to hack a solution in the final few hours and won the whole thing (Go team lolwamen!!).

Problem

Initial Analysis

$ file trig

trig: ELF 32-bit LSB executable, Intel 80386, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib/ld-, BuildID[sha1]=be9f9521d9010aa32e53457121ba102647593600, stripped

Looks like an x86 executable. Let’s disassemble and see what’s inside.

$ objdump -d trig

trig: file format elf32-i386

Disassembly of section .text:

0804814f <.text>:

804814f: 58 pop %eax

8048150: 58 pop %eax

8048151: 5c pop %esp

8048152: db 44 24 0c fildl 0xc(%esp)

8048156: 61 popa

8048157: 68 00 ff 3f 00 push $0x3fff00

804815c: 50 push %eax

804815d: 68 80 80 80 80 push $0x80808080

8048162: dd 44 24 03 fldl 0x3(%esp)

8048166: d9 ff fcos

8048168: 89 4c 24 04 mov %ecx,0x4(%esp)

804816c: dd 44 24 03 fldl 0x3(%esp)

8048170: d9 ff fcos

8048172: 89 54 24 04 mov %edx,0x4(%esp)

8048176: dd 44 24 03 fldl 0x3(%esp)

804817a: d9 ff fcos

804817c: 89 5c 24 04 mov %ebx,0x4(%esp)

8048180: dd 44 24 03 fldl 0x3(%esp)

8048184: d9 ff fcos

8048186: 89 6c 24 04 mov %ebp,0x4(%esp)

804818a: dd 44 24 03 fldl 0x3(%esp)

804818e: d9 ff fcos

8048190: 89 74 24 04 mov %esi,0x4(%esp)

8048194: dd 44 24 03 fldl 0x3(%esp)

8048198: d9 ff fcos

804819a: 89 7c 24 04 mov %edi,0x4(%esp)

804819e: dd 44 24 03 fldl 0x3(%esp)

80481a2: d9 ff fcos

80481a4: dd 5c 24 06 fstpl 0x6(%esp)

80481a8: dd 5c 24 0c fstpl 0xc(%esp)

80481ac: dd 5c 24 12 fstpl 0x12(%esp)

80481b0: dd 5c 24 18 fstpl 0x18(%esp)

80481b4: dd 5c 24 1e fstpl 0x1e(%esp)

80481b8: dd 5c 24 24 fstpl 0x24(%esp)

80481bc: dd 5c 24 2a fstpl 0x2a(%esp)

80481c0: dd 5c 24 fe fstpl -0x2(%esp)

80481c4: bb 01 00 00 00 mov $0x1,%ebx

80481c9: 8d 4c 24 fc lea -0x4(%esp),%ecx

80481cd: ba 02 00 00 00 mov $0x2,%edx

80481d2: bf 30 00 00 00 mov $0x30,%edi

80481d7: 4f dec %edi

80481d8: 78 1c js 0x80481f6

80481da: 8a 04 3c mov (%esp,%edi,1),%al

80481dd: c1 e0 04 shl $0x4,%eax

80481e0: 8a 04 3c mov (%esp,%edi,1),%al

80481e3: 66 25 0f 0f and $0xf0f,%ax

80481e7: 66 05 61 61 add $0x6161,%ax

80481eb: 50 push %eax

80481ec: b8 04 00 00 00 mov $0x4,%eax

80481f1: cd 80 int $0x80

80481f3: 58 pop %eax

80481f4: eb e1 jmp 0x80481d7

80481f6: b8 04 00 00 00 mov $0x4,%eax

80481fb: ba 01 00 00 00 mov $0x1,%edx

8048200: 6a 0a push $0xa

8048202: cd 80 int $0x80

8048204: 58 pop %eax

8048205: b8 01 00 00 00 mov $0x1,%eax

804820a: 31 db xor %ebx,%ebx

804820c: cd 80 int $0x80

Notice that there are 7 fcos ops in the assembly, which is basically an inplace cosine operation. The floating point instructions like fcos, fldl, fstpl... belong to the x87 instruction set. Also, the binary takes a command line argument and returns a string of fixed length (96).

$ ./trig gibberish

cpefdefhgfbpdphdehmafmpndpbfmlnkbcjedpdhbecjbjdkdppgngeohipeepbamjgpcenfdpcmiagldjonbebnfffbfbae

Now, we can just reverse engineer whats happening by studying the x87 ops and carefully looking at assembly instructions, but who wants to do all that.

Ditch the assembly

We’ll explore a different route. We noticed that output stops changing when length of input argument exceeds 32 characters. Also, shifting the argument by a factor of 4 seems to shift some output chars in the opposite direction.

With some trials, we figure out that, an input string ABCDEFGH (A, B, . . represent a block of 4 characters) is mapped to f(H)f(G)f(F)f(E)f(C)f(B)f(A)p(D). Here, \(f(X) \neq p(X)\) and output of both is 12 characters in length.

This leads us to the conclusion that if we can just find out the mappings \(f, p\) and invert them, we get the flag.

Brute Force Attack :)

First, we need a wordlist, so we generate one.

import os

from tqdm import tqdm

charset = "0123456789abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ!?@_" + '{' + '}'

n = len(charset)

with open('wordlist.txt', 'w') as f:

for i in tqdm(range(n)):

for j in range(n):

for k in range(n):

for l in range(n):

f.write(charset[i]+charset[j]+charset[k]+charset[l]+'\n')

There are 21381376 words, this’ll take some time.

Second, we need to find the output for each of these words and check for a match in our given output. In 1 call to the executable, we can get outputs for 7 4-char blocks. Running the binary from C++ or Python is easy, but if you also read stdout, it costs time. So, I just write the output in a new file for reading it later because I couldn’t find the C++ way to read stdout without the slow Popen().

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

/*

Template: ggggffffeeeexxxxddddccccbbbbaaaa

*/

int main()

{

int n = 19545240;

string words[8];

string line = "";

string cmd;

string base_cmd = "./trig ";

ifstream wordfile;

wordfile.open("words.txt");

for (int i=0; i < (n/7); i++)

{

for (int j = 0; j < 8; j++)

{

if (j == 4)

{

words[j] = "xxxx";

}

else

{

getline(wordfile, words[j]);

}

}

for (int j = 0; j < 8; j++)

{

line = line + words[7 - j];

}

cmd = base_cmd + line + " >> outputs.txt";

const char *command = cmd.c_str();

system(command);

line = "";

}

wordfile.close();

return 0;

}

It takes around 80 minutes to finish on my laptop (Ryzen 5 3550), but still much less than it took me to reverse the assembly.

Cleaning Up

Now, we just have to match the outputs to the required outputs and recover the input ezpz.

from tqdm import tqdm

output = "ephcmbhkmemndpkagnebjbcbdpcbglelpnfpdpcbokhpdbahdpfpdjboemeodpkehfphfbhcdpfmpmbpifdkbeimmdpkjjai"

result = [output[12*i:12*i+12] for i in range(7)]

lines = 2792177

with open('words.txt', 'r') as f:

words = f.readlines()

lookup = {}

s = []

with open('outputs.txt', 'r') as f:

for l in tqdm(range(lines)):

a = f.readline()

a = [a[i*12:i*12+12] for i in range(7)]

for i, k in enumerate(a):

if k in result:

lookup[k] = words[7*l+i][:-1]

s.append(7*l+i)

flag = ''

for i in result[::-1]:

if i in lookup.keys():

flag += lookup[i]

print(flag)

$ python3 match.py

100%|██████████████████████████████████| 2792177/2792177 [00:08<00:00, 313834.23it/s]

CsecIITB{H0pu_l34rn3d_R1ght}

But, this is not the flag. That’s because we only found the mapping \(f\). Finding \(p\) would have taken 7 times longer. We know we are missing a 4-char block, we know the position too. We can make some educated guesses for the missing block, it’s not that hard.

Flag

CsecIITB{H0p3_y0u_l34rn3d_R1ght}

See, assembly is overrated. Warm up your processors instead.

Comments